Receiving a rejection notice for your research paper is a frustrating and disheartening experience. After months or even years of work, a rejection can feel like a personal failure. But what if you could reframe it? A rejection is not a verdict on your value as a researcher; it is a diagnostic tool. It’s a set of expert feedback telling you exactly what needs to be fixed.

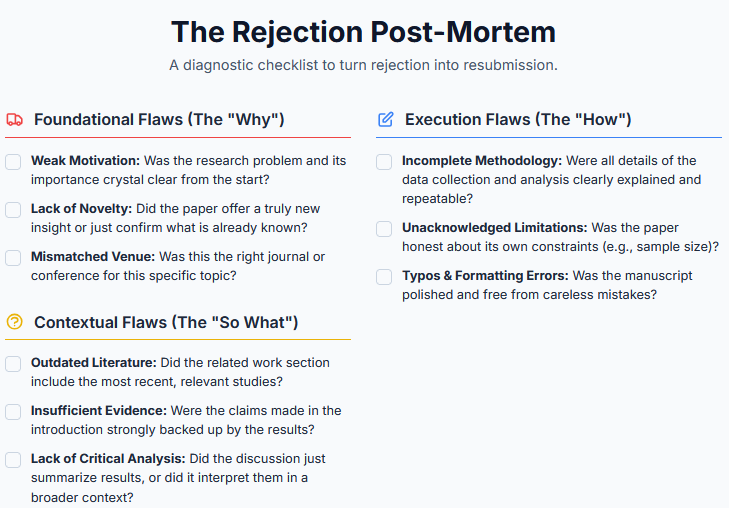

Many papers are rejected not because the research is poor, but because of fixable issues: an unclear research gap, a weak methodology, or a poorly structured manuscript. By understanding the common reasons for rejection, you can learn to diagnose the weaknesses in your own work and turn a frustrating setback into a successful resubmission.

This guide will walk you through a systematic process for understanding why papers get rejected and how you can strengthen your manuscript to dramatically increase its chances of acceptance.

Part 1: Diagnosing the Foundational Idea

Before a reviewer even looks at your methods or results, they assess the core premise of your work. Flaws at this foundational level are often the most critical.

- The Problem: Weak Motivation or Unclear Contribution

This is the most common reason for a desk rejection. The reviewer is left asking, "Why does this research matter?" If the paper fails to articulate a clear research gap, explain the importance of the problem, or state who will benefit from the findings, it lacks a compelling reason to exist.

- The Fix: Your introduction must tell a powerful story. It should start with a broad, important problem and logically narrow down to a specific, urgent gap in the literature. Explicitly state your research question and contributions upfront. Don't make the reviewer guess why your work is important—tell them directly.

- The Problem: The Results Are Not Sufficiently Novel

Your research may be methodologically sound, but if your analysis generates findings that are already well-established, it offers no new contribution to the scholarly conversation. This can happen due to a limited dataset or a methodology that isn't capable of producing novel insights.

- The Fix: Before you even begin writing, you must be confident in your novelty. This means conducting a thorough literature review to understand the current state of the art. When you write your paper, you must explicitly differentiate your findings from previous work, highlighting exactly what new knowledge your research adds.

Part 2: Diagnosing the Scholarly Context

A paper doesn't exist in a vacuum. It must be positioned within an ongoing conversation in your field. Failure to do so is a major red flag for reviewers.

- The Problem: The Literature Review is Outdated or Incomplete

This is one of the most common—and easily avoidable—reasons for rejection. If you fail to include the most recent and relevant studies, it signals to the reviewer that you are not fully engaged with the current state of your field.

- The Fix: Make your literature search an ongoing process. Before submitting, do one final sweep of recent publications to ensure you haven't missed any critical papers. Your work must be in dialogue with the very latest research.

- The Problem: The Paper Lacks Critical Analysis and Depth

A research paper is more than a summary of findings; it's an argument. Many papers are rejected because they simply report results without interpreting them. The discussion section may lack depth, fail to engage with alternative explanations, or neglect to connect the findings to broader theories.

- The Fix: Your discussion section should be the most thoughtful part of your paper. Don't just restate your results. Interpret them. What do they mean? How do they challenge or support existing theories? What are the practical or theoretical implications? This is where you demonstrate your intellectual depth.

- The Problem: The Paper is Not Relevant to the Target Venue

You may have written a brilliant paper, but if you submit it to a journal or conference whose scope doesn't align with your topic, it will likely be desk-rejected.

- The Fix: Do your homework. Carefully read the aims and scope of your target journal. Skim through recent issues to get a feel for the types of articles they publish. Submitting to the right venue is one of the easiest ways to increase your chances of success.

Part 3: Diagnosing the Manuscript Execution

Even with a strong idea and good context, a poorly executed manuscript will be rejected. These flaws signal a lack of care and undermine the credibility of your work.

- The Problem: The Methodology is Missing Information

If a reviewer cannot understand exactly how you conducted your research, they cannot trust your results. A methodology section that lacks key details about data collection, analysis methods, or the dataset itself is a recipe for rejection.

- The Fix: Your methodology section should be a clear, step-by-step recipe that another researcher could follow to replicate your study. Be precise, be thorough, and leave no room for ambiguity.

- The Problem: The Claims Are Not Supported by Sufficient Evidence

It's easy to make big, exciting claims in your abstract and introduction. But if those claims are not fully supported by the evidence presented in your results section, reviewers will lose confidence in your work.

- The Fix: Be honest and precise. Ensure that every claim you make is directly and robustly supported by your data. It's better to make a smaller, well-supported claim than a grand one that collapses under scrutiny.

- The Problem: Limitations Are Not Acknowledged

No study is perfect. Failing to acknowledge the limitations of your research (e.g., sample size, methodological constraints, generalizability) is a major red flag. It suggests a lack of critical self-awareness.

- The Fix: Include a dedicated "Limitations" or "Threats to Validity" section. Discuss the boundaries of your study transparently. This doesn't weaken your paper; it strengthens your credibility by showing you are a thoughtful and honest researcher.

- The Problem: Careless Errors, Typos, and Formatting Issues

Typos and grammatical errors are the easiest flaws for a reviewer to spot, and they immediately signal a lack of professionalism and care.

- The Fix: Proofread your paper multiple times. Read it out loud. Use tools like Grammarly. Ask a colleague to read it one last time before you submit. A polished, error-free manuscript makes a powerful first impression.

Final Thoughts

A rejection is not an endpoint; it's a data point. It provides invaluable feedback that, if used correctly, can make your work stronger. By systematically diagnosing your paper against these common reasons for rejection, you can turn frustration into a focused plan for revision and, ultimately, publication.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- How should I respond to reviewer comments after a rejection?

First, take a day to absorb the feedback without reacting emotionally. Then, create a "response to reviewers" document. Go through each comment, one by one. Thank the reviewer for their suggestion, state how you have addressed it in the revised manuscript (e.g., "We have now clarified our methodology in Section 3.2"), and provide a brief rationale for your change. This systematic approach shows the editor you have taken the feedback seriously. - The reviewers gave contradictory advice. What should I do?

This is common. In your response document, acknowledge both points. Then, state which path you chose to take and provide a clear, logical justification for your decision. For example, "Reviewer 1 suggested X, while Reviewer 2 suggested Y. We have chosen to implement X because it aligns more closely with our study's primary objective. We have explained this rationale in the discussion." - After a rejection, should I resubmit to the same journal or try a different one?

It depends on the editor's letter. If the editor offers a "reject and resubmit" decision, they are inviting you to revise the paper for reconsideration. This is often a positive sign. If it is a hard rejection, it is usually better to revise the paper based on the feedback and submit it to a different, more suitable journal.